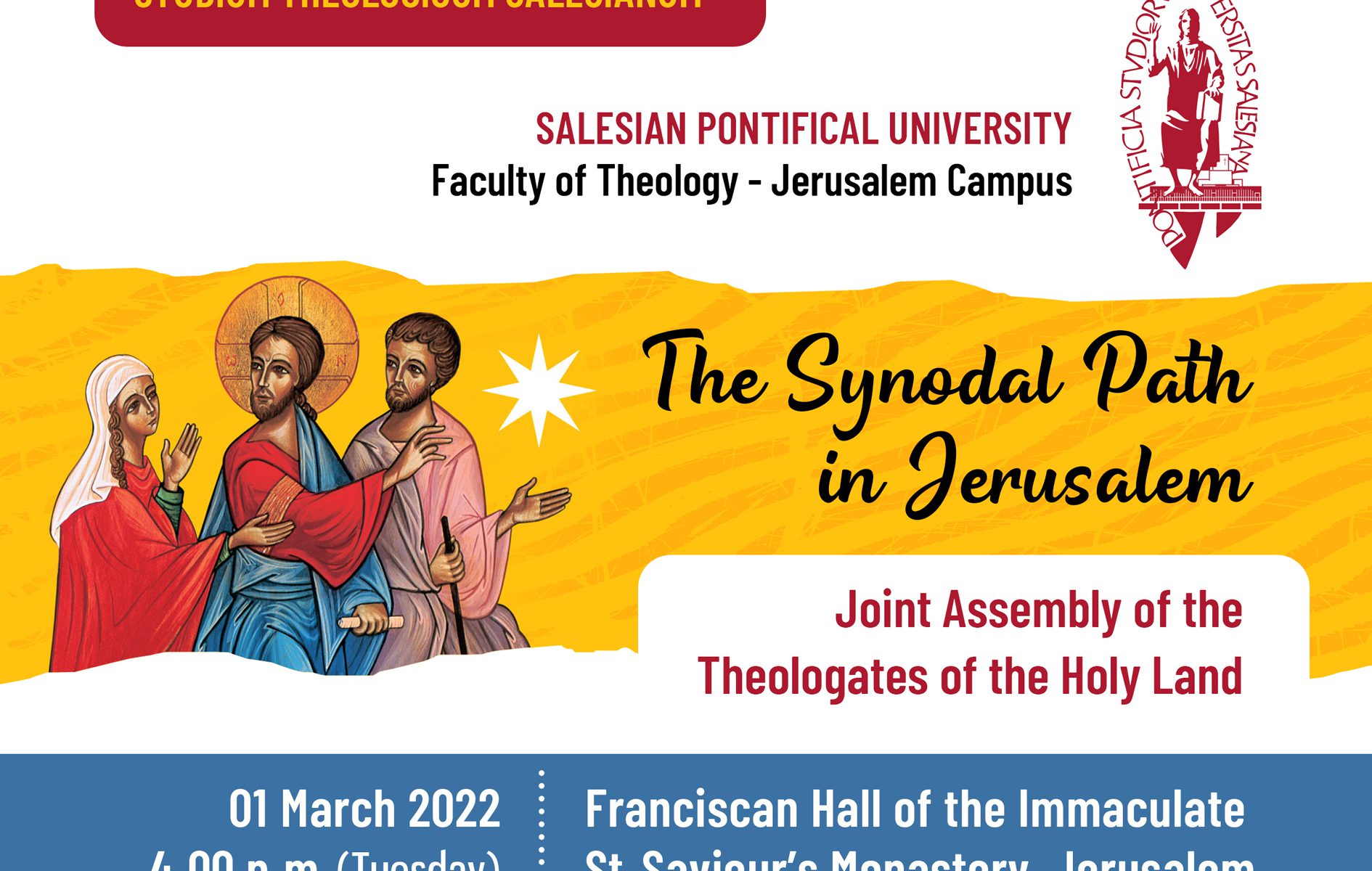

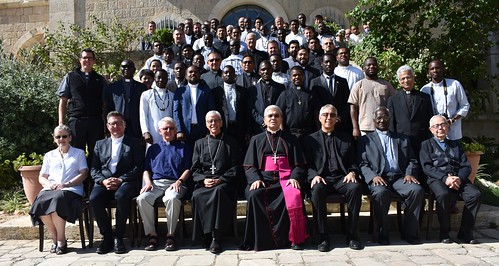

Speeches presented at the joint assembly of the Theologates at the Holy Land

SYNODAL PATH IN JERUSALEM

A list of the Speakers are given below:

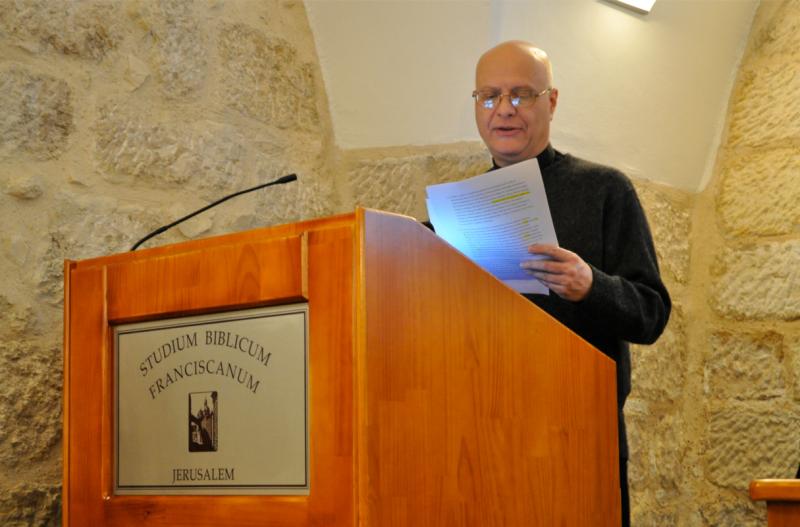

1. Rev. David Neuhaus SJ : 'The Synod and Learning to Listen'

2. Rev. Amjad Sbarra OFM : 'The Synod and Mission of the Church'

3. Ms Saswan Bitar : 'The Synod, Women and Ecumenism'

4. Ms Nadine Bitar : 'The Synod, Youth and Laity'

5. Mr Dima Ezrohi : 'The Synod, Hebrew Speakers, Migrants and Diversity'

6. Ms Dima Kalak : 'The Synod, and the Marginalized'

Father David Neuhaus SJ: The coordinator of the Synod Preparatory Committee.

The Synod and Learning to Listen

In the Vademecum, the Official Handbook for Listening and Discernment in Local Churches, it says: “The Synodal Process is first and foremost a spiritual process. It is not a mechanical data-gathering exercise or a series of meetings and debates. Synodal listening is oriented towards discernment. It requires us to learn and exercise the art of personal and communal discernment. We listen to each other, to our faith tradition, and to the signs of the times in order to discern what God is saying to all of us.” (2:2).

Central to the Synodal process is learning to listen. We are called to admit that we are not so good at this. We are formed to talk, to preach, to teach, to encourage, to reprimand. We talk a lot, perhaps a lot too much. We feel uncomfortable with the silence that is necessary to allow others to speak. We feel driven to fill the silence with words, our own. This blocks out the voices of those who want to speak, who need to express themselves, those for whom and with whom we must become Church. The Synod seeks to allow these voices to emerge, to be heard, to perhaps provoke discomfort but to ultimately lead us to a more authentic way to be Church in our age.

At the Transfiguration, the disciples gazed on the Transfigured One and heard the voice saying: “Listen to Him”. However, the Resurrected One then came among the disciples and listened to them on the way to Emmaus. He only then responded to them, hearing their pain, their sense of being abandoned, their despair. In listening, we must learn to discern, discern the voices from our own, discern the myriad voices that address us, distinguishing where we are being led.

The synodal process seeks to renew our ability to listen in a world that is very noisy indeed. In order to listen, we must discern His voice among the voices, distinguishing His voice from the cacophony of voices that try to derail us. His voice is the voice the gives life, that opens the horizon that seems shut, that offers good news in a world that too often plunges us into despair.

Listening is contextual. The context for listening is the communion that unites us, in which we must all participate. Listening must be renewed, relearned, reappropriated in each generation so that the Spirit can breathe life into the Word in the midst of our world, the world in which we live and move and have our being. It is in the communion that is enabled by listening that we become a community, participating together as one body in the life of Christ our head, who sends us on the mission of bringing Him into the world so that it can be redeemed.

Let us listen to Him with ears opened a new, with hearts aflame and with rekindled desire to follow him. Let us hear him in all the usual places: in the Scriptures; in the Church; in our hierarchy (the Holy Father, the bishops, priests and deacons) … but let us also listen to Him with renewed commitment in our communities (religious, parish and families and friends), in the encounters in our apostolates (schools, hospitals, youth ministry, homes and social outreaches). Let us seek Him out in the world beyond the borders of our institutional Churches, among other Christians, among the believers of other religions, among those who no longer believe or have never believed and yet have much to teach us. Let us go especially to the margins, among the forsaken, the abandoned, the poor and the hopeless for we know that there he awaits us to offer us guidance and comfort!

Father Amrad Sbarra OFM

The Synod and the Mission of the Church

1- The Mission of the Church is to break through the darkness of the world with the light of Jesus Christ, and to let everyone understand and reveal God’s design for Healthy and holy relationships.

2- Hearing the anxiety and demands of the people.

3- In answer of the anxiety on the problems, the church is called to provide the people with tools to protect their life and the life of their families, by helping those in need and answer the call and the will of God’s call to be leaders in the world and to deal with challenges, to survive with the grace of the Holy Spirit.

4- Empowering each other to be key partners in success, and a guardianship for everyone in need.

5- The Church must teach strategies which has been founded Through meditation on the word of God, to achieve the best results for improving the worldview and the sets of thoughts for everyone who is related to the Church.

6- This is the path of the Synod in which we are capable to give each one of us a role to be a part of a better world.

Ms. Sawsan Bitar

The Synod, Women and Ecumenism

I am so thrilled to be part of this important event, though it comes at a time of uncertainty in so many ways, the current pandemic, unemployment, limited resources … etc. On the other hand, it has brought some hope to people whose voices are not usually heard in the church., people who are very tired, and disappointed.

As a woman of faith, I would like to share with you what it means to me personally to be walking this journey. I will start by reflecting on the story that was chosen to guide us in the synod, and the powerful image that was used, “the Way to Emmaus”.

Two disciples, a man and a woman are walking together, sad, heartbroken and disappointed because of the injustice that happened to their teacher. Jesus comes and walks with them and listens to their concerns. This picture has brought hope to me and I said to myself, by the will of God it is the beginning of equality in the Church, having women and men on the same level in ministry is something that I have always dreamt to see in my church.

Our mission now is to help more women to be involved in the church, with no fear of discrimination between women and men. “We are equal”. Let us start walking together with our Bishops and Priests on changing all discriminating rules and actions between the people of God, because this is what Jesus taught us.

From now on, I think it is not possible to go backwards. It is about time to reach out to women who are far away from the church and to listen to one another, to the Word of God and the Holy Spirit. We must create a healthy environment for them to feel safe in sharing what is going on in their hearts and minds as Jesus did with the two disciples of Emmaus, and to walk together towards a better future for our community and the Church.

I have also been involved in the Ecumenical journey for almost 25 years. I remember when I started as a coordinator for the Clergy Program at Sabeel - the Ecumenical Liberation Theology Centre - I was afraid of not being accepted as a woman to bring together Heads of Churches and parish Priests from all traditional churches in one gathering, whether it is a meeting, a conference, a spiritual retreat or a worship service. By the grace of God, things have changed. We have reached a point where I now, confidently, organize ecumenical worship services, conferences and retreats for clergy from different church denominations.

Being part of the synod committee - walking together towards ecumenism - I am trying to spread the word to other churches through our Ecumenical programs.

On October 22nd and 23rd, we had the Annual Clergy Retreat that took place in Jericho. Forty-two clergymen and their wives from the West Bank, Galilee and Jerusalem, representing the different churches, attended this retreat. One of the sessions was led by Emeritus Patriarch Michael Sabbah in which he introduced the Synod to the participants. His talk was very powerful and he explained what this Synod means for them as Clergy. He encouraged the priests from the different denominations to listen to one another and to all people of faith in order to reduce the gap between them.

The priests usually speak about themselves as ‘we’ and the lay people say ‘them’, and it is now time to say ‘us’. Because all of us together are the church.

The second event was the Sabeel Annual Ecumenical Christmas dinner where we had around two hundred people including Bishops and clergy from the different denominations. The Christmas message was given by Sister Ghada Nehmeh, a member of the Synod committee. In her message she spoke about the synod and the importance of the ecumenical spirit and the work among the people of faith.

We are also trying to involve young people in the spirit of ecumenism by organizing special ecumenical worship services for the students in the different Christian schools. So far, we have had two services. The students were so happy to see the Bishops and Priests from the different traditions pray together with them. This program was organized jointly with the Catechetical Office of the Latin Patriarchate.

I hope and pray that one day we will all be united as one Body of Christ. The Synod encourages us to dream and this is my dream!

Ms Nadine Bitar

The Synod, Youth and the Laity

Allow me first to introduce myself, my name is Nadine Bitar- Abu Sahlia, I was born and raised in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem but after I got married, I moved to live in Reineh a small village between Nazareth and Kofer Cana. I obtained a BA in Youth Ministry and a master’s degree in Christian Ministry from North Park University/ Seminary in Chicago, Illinois. I worked for Terra Sancta Schools Central Office for two years. I currently work at the Catechetical Office of the Latin Patriarchate and also serve as the General Secretary of the Christian Youth in Palestine “The Youth of Jesus’ Homeland”.

I am standing here today to deliver the voice of my fellow youth who have been for so long disconnected from the Church due to many challenges that they have faced when it comes to expressing their faith or just for trying to get spiritual help from a consecrated person. Unfortunately, we have lacked the message of our church’s Synod for years, and allow me to be honest with you, it will not be an easy task to restore this message. As I was reading the Spiritual conversation of this Synod, I could clearly see its main focus, active listening. For the past 20 years I have searched for so long for a consecrated person who is willing to accept me as I am. I am not saying that we do not have those persons in our diocese, we do, but we need more of those people to help the youth find refuge in our churches.

The spiritual conversation document says the following: “the spiritual conversation focuses on the quality of one's capacity to listen as well as the quality of the words spoken. This means paying attention to the spiritual movements in oneself and in the other person during the conversation, which requires being attentive to more than simply the words expressed. This quality of attention is an act of respecting, welcoming, and being hospitable to others as they are. It is an approach that takes seriously what happens in the hearts of those who are conversing. There are two necessary attitudes that are fundamental to this process: active listening and speaking from the heart.”

Based on the most recent study done by Juhod Foundation, having YJHP and the Catechetical office as partners for this study. We have come to one of the most unexpected percentage of 57% of the youth have lost their trust in the church authorities and any activities done through a church-based organization. This number should be concerning, and it needs to be discussed as we work on the Synod now and for the years to come. In fact, YJHP has been doing the work of the Synod years before the Vatican has thought about the idea.

We, the youth, do not only need someone to speaks to us from the heart, we also need someone who is willing to accept us from the heart. Someone who allows us to speak from the heart, without fearing the judgmental look of the person hearing. Many of our youth have experienced the lack of the listening process in our church’s for so long that they do not know how it feels like to be listened to. We need action to make sure that our words were heard. Just like faith is incomplete when it is not brought out through action and so is listening, it’s incomplete when no action is taken to fix what was broken. For this reason, YJHP has been working on establishing a headquarter centre for the youth to find refuge in. The main purpose of this centre is to create a safe haven for the youth. To make them feel welcomed and accepted. To make them feel that they are respected. To make sure that they are in a place that would pull them back from the darkest periods of their lives into the light of God. This centre has been our dream for years, and as part of the church’s action towards fulfilling the needs of the youth this centre should be its priority. We need your support to help those who live in exile away from the church even though it is within walking distance from them.

I pray to our Heavenly Father, to help those youth discover His presents in their lives. In addition, to the Holy Spirit to help us and guide us to reach our goal of creating a youth centre that will serve the youth, despite of their backgrounds. Our dream is to see the youth of Jesus’ Homeland spiritually alive to restore the church relationship with them.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mr. Dima Ezrohi

The Synod, Hebrew Speakers, Migrants and Diversity

The synodal process is taking place in the vicariates of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem for Hebrew-speaking Catholics and for migrants and asylum seekers. Of course, although we speak only of two vicariates, the reality is much more complex: the Vicariate for Migrants and Asylum seekers encompasses a vast array of communities – Philippine, Indian, Sri Lankan, Eritrean, etc. – each with its concrete reality and, therefore, its synodal process, in a way. Given that there aren’t many native Hebrew speaking Catholics, the same is true for the St. James Vicariate – every community, even every believer, embodies a different reality in the church’s life. However, I’m not here to do PR services for my Vicariate in front of His Beatitude or Fr. David.

Today I want to speak to the future priests of the Patriarchate and say that a synodos also has to be an exodos: we have to go out to meet each other so that we can walk together. The migrant and Hebrew speaking communities cannot undergo the synodal process independently. It simply will not happen by each migrant community sitting in its church – or, more realistically, the apartment they rent a chapel – and thinking for itself. We are one church, and so we need to have one journey. The situation is complicated: although in the political landscape the Hebrew speaking society to which both vicariates firmly belong is the regional hegemon and majority, the situation is reversed in the life of the church; suddenly – the substantial majority turns to a minority and demands to be recognised as a partner for a journey. This is a difficult task: I can understand why a Palestinian Christian, who has enough refugees in his vicinity, might not pay much attention to the plight of Sudanese or Eritrean asylum seekers in Tel-Aviv or my dear friends who right now make their way out of the carnage fields in Ukraine. We all have a lot on our plate, especially the Palestinian people, so to demand from the Arab-speaking majority to make a place for us as partners for the way is to request something difficult. Unfortunately, Jesus never promised us an easy journey.

The Patriarch spoke about the church being a laos and not a demos: a people convoked, called out (ek-klesia), and not a social reality like the state or the polis. Sometimes we risk becoming a demos by letting political and ideological issues – hard though they are – decimate the church's unity from within. However, this is not only an obligation but also – and mainly – a gift. When we listen to the voices from the peripheries, we enrich ourselves. I always think of the image of the People coming to the civilised land of Canaan from outside, from the desert, from the limes, the limit. This is the biblical perspective, and it should be ours as well.

Actually, if we dare walk together, we will discover that there is something that unites all Christians in this land: our crosses. The experience of migration, being a fugitive, economic hardships, suffering from the unexpected twists and turns of life, and being the minority in a non-Christian society – all this is common, in some way at least, to all of us. When I teach catechism to migrant children in south Tel-Aviv, I often use a YouTube video that depicts Christ’s work of salvation on the cross: there is an abyss, we are on one side, God is on the other, suddenly, the cross descends from above and forms a bridge, a delicate but tangible pathway between both sides. This is what the cross can do for us; it can make us recognise our shared identity.

Last but not least: I want to talk about imagination. The Holy Father talks a lot about us daring to dream about the church of the future. But, before we can dream of the future of our local church, we must be able to imagine the reality of our catholic neighbour. Can you and I know it might be controversial to say, imagine the reality of an 18 years old Filipino Catholic whose most significant concern in life right now is her upcoming service in the IDF? Not only that, who dreams and prays to God to be stationed as a combat soldier, together with her Jewish friends? I know it is a harsh reality for my Palestinian sisters and brothers, but it is the reality of the Church. This young woman comes to the church and seeks answers, advice, accompaniment. Can we imagine her situation? We have to; she is a member of the body of Christ, as much as anyone else. Of course, her dreams might have been different had she met her sisters and brothers from the Palestinian side. She might have formed a more aware and complex picture of the situation in our beloved land. However, we didn’t give her a chance to meet them because we were overwhelmed by the difficulties, the divides, and daily realities. Finally – let us all walk together, it will not be easy, but it is the only way.

Ms Dima Kalak

The Synod and the Marginalized

What makes this Synod a bit more special than any other previous synod is the fact that it came at a time when people are still struggling with COVID19.

This pandemic has affected every one of us differently whether in terms of health, or socially, emotionally, economically – it has affected our parents, children, friends, neighbours, and the list can go on.

In one way or another, we have all become vulnerable in our way. For the last two years, vulnerability became even more obvious among those who were already struggling. Professionally, as a social worker, I think it has been one of the most challenging periods because of the level of marginalization and vulnerability that we have witnessed in the Holy Land was unprecedented.

For months, I was not able to welcome people or see them face-to-face and had to spend hours on the phone doing what I can to support these people. It was not easy. Many heads of households panicked because they could not provide basic needs to their families whether because they have lost their jobs or main source of income. Couples struggled with their marriage, I was hearing more and more about marital problems including fighting, arguing and even physical violence. Many of elderly grandparents who were already struggling with loneliness and had to be isolated from loved ones for prolonged periods. Many of our children have lost focus in virtual education and many did not even have the means to connect like their peers to online classes. Many people feel ill in one way or another- their illness ranged from light or grave- for some of the people they suffered as they saw their family members becoming ill. There were families who have even lost loved ones unexpectedly.

For me today, the Synod is more than a spiritual journey for the church. Restoring faith is of course part of it but restoring hope to the people who have struggled is also part of this journey. The Catholic Church has played a critical role in the restoration of this hope and continues to do so even till today. The role that we play is an important one towards these vulnerable and marginalized whether providing basic needs, or group and individual counselling sessions or short-term job opportunities, medical support, medication and much more. The need was so immense.

I was even encouraged by the solidarity and responsiveness of many families who wanted to help those who were struggling; many of the local Christian families have donated goods, clothes, or even cash to help us reach out the largest group of people possible. A very powerful witness for feeling with the others.

Even if the pandemic ends today, there is a lot of rehabilitation that we have to do as part of the synod. So how can we continue this journey of restoring hope to those marginalized? How can we mainstream this Synod to those marginalized? The first and most important things that we need to do is to Focus: we need to get these vulnerable people back on our top priority list deliberately and intentionally. This includes all those who are suffering: families, children, women, etc. For the last two years, our daily routine has changed so much that may have lost some focus; before we start the journey, we need to get our people right in front of us. Become focused and stay focused!

Healing through listening: there is so much brokenness out there; people continue to struggle in one way or another; there is so much healing to do with these people. The first step towards healing is listening. Not every person who approaches us wants money. Many need ears and hearts to listen to them with their struggles; couples are burdened, elderly continue to struggle and the first step towards their healing is that we listen to what they have to say. Open the doors of your homes, churches and hearts…

Reaching out is another critical part. Not every person who struggles will come to us. We must look into the horizon to the marginalized who we may have gone missing for the last two years- from the community, church, society, club, society. Some people may no longer be able to come to us for health or others who have socially felt left out and no longer find a place. Let us leave our comfort zone to find these who need the help and support. Even when find resistance from people who may be hurting, at least we have done our part. Do not be afraid to go out to find them.

Action and prayer: once we have restored focus, made ourselves available and reached out, we should by then know what these people really need. If it is more than listening, it is time to take action: support maybe emotional or financial or even help people who struggle with their faith and need a prayer.

In all that we to assist these marginalized, we are humbled by our calling to be Christlike – to welcome people who are weary and help them carry their burdens. Here we are called to put them first and being there for them as it is necessary.

1st March, 2022